Elixir's Modularity Toolbox

Elixir is one of few languages that provides an almost complete set of modular abstractions. In this post I aim to provide a description of different ways of achieving modularity in Elixir for different application sizes, with usage notes and examples. We’ll also look at a simple example of an app moving from one modularity “level” to the next over time, and will try some tools that will help us understand modular structure of our apps better.

Table of Contents

- What’s modularity?

- Modularity levels

- Level 0. One module

- Level 1. A collection of modules

- Level 2. Modules with submodules

- Level 2.5. Contexts

- Level 3. Behaviours

- Level 4. Actors

- Level 5. Applications and Umbrella Projects

- Level 6. Components

- Special case: Dispatch through configuration

- Architecture shouldn’t be set in stone

- No “just in case” design

- Tools that are helpful for tracking and improving modularity

What’s modularity?

To talk about modularity, we need to define it first. I consider modularity to be a spectrum, thus defining it in terms of its range seems reasonable.

Non-modular code – is a code which:

- is highly interconnected – there is no or very little/inadequate separations of logical units from each other. Modules, if those are used, have low cohesion, and a lot of dependencies/dependents. Different concerns are not separated; one module may be doing several unrelated things.

- contains a lot of implicit contracts between different parts of code – often manifested via dependency of one part of the code on order/duration of side-effects in another part.

- has a pattern of failures in one part making unrelated parts crash

- is becoming disproportionally harder to understand, change and maintain the larger it grows – everything affects everything, changes tend to have a cascade effect, and each additional feature is complicating existing code even further.

Highly modular code – is a code in which:

- logical units are separated, and each of those modules has as few dependencies as reasonable, and high cohesion

- contracts between modules are explicit

- failures in one part of the code don’t cause unrelated parts to fail

- is becoming proportionally harder to understand, change and maintain the larger it grows

At the same time, non-modular code in the small is often easier to read and maintain, and highly modular code is often longer and sometimes harder to follow, especially when abused.

Non-modular code is also faster to write until certain sizes, and sometimes results must be achieved as fast as possible ; in these cases writing non-modular code in a crisis is ok, as long as after the crisis end this code will be fit back into shape.

Thus, modularity is something that becomes more important the larger code grows, and excessive modularity may hurt developer productivity and performance.

Modularity levels

There are conventions for implementing different levels of modularity in the Elixir community, though the whole “levels” nomenclature is my own attempt at categorizing those conventions. Selecting an appropriate level of modularity for some code is easier when those levels are well-defined, so what follows is my attempt of defining those levels.

Each level is described in terms of the best possible implementation. You can easily have non-modular code, yet use behaviours all over the place, - implicit contracts and failure modes can bite at any code organization level.

Note: I use “app” when I talk about a “program”, and “application” when I talk about an Elixir application in the following sections.

Level 0. One module

Nuff said.

Applying classic top-down programming is extremely beneficial at any level, including this one - and helps with transitioning to the next one, if the app grows.

Example: To better demonstrate how an app can be refactored by moving from one modularity level to the next, let’s take an example of a simple chess server. Let’s start with just one module:

+ chess/

config/

+ lib/

chess.ex

test/

mix.exs

Default Elixir folder structure that you can get from mix new chess.

Let’s assume that for now we concentrate on a console app. By applying top-down design we can arrive at something like this in a couple of minutes:

defmodule Chess do

def play() do

play(init_board(), first_turn_player(), 0)

end

def play(board, player, turn) do

move = read_move(player)

case execute_move(move, board, player) do

{:ok, new_board} ->

if checkmate?(new_board) do

declare_victory(player, turn)

else

play(board, next_player(player), turn + 1)

end

{:error, illegal_move} ->

report_illegal_move(player, illegal_move)

play(board, player, turn)

end

end

## IO

def read_move(player), do: nil

def report_illegal_move(player, illegal_move), do: nil

def declare_victory(player, turn), do: nil

## Players

def first_turn_player(), do: nil

def next_player(player), do: nil

## Game logic

def init_board(), do: nil

def checkmate?(new_board), do: nil

def execute_move(move, board, player), do: nil

end

Now, you may decide that you want to store board, current player, and turn in a struct (which you can do in a submodule in the same file – when starting, it’s often helpful to keep things close), or separate functions/name things slightly differently, but the design process is the same: we start with global loop, and recursively drill it down until each functions becomes small enough to tackle. execute_move in particular will probably need splitting into several helpers eventually.

We also group together IO and related pieces of logic. Of course, you should also try to minimise the number of impure functions starting even from this level – IO tends to change quite a bit during development, and testing pure functions is easier.

I would then write typespecs for those functions, and return some default data from each of those. After that I will work on a concrete implementation, and finally I will add docs.

Later on you may want to make most functions here private to specify precise module boundary, but during initial development it’s especially helpful to be able to play with each function in IEx.

When to use: small scripts, demonstrations of simple algorithms, tiny small command line tools, etc.

Level 1. A collection of modules

A simple collection of modules. Often there’s application.ex, or main.ex, or similar file there, that starts some workflow, using other modules.

At this level issues of modular design start to become relevant. We are levelling up our modular design game by separating logical units of code from each other.

Starting from this level, it’s important to be mindful of dependencies between those modules. Good modular design emphasises minimal dependencies between modules, and high cohesion in each module.

Example: Continuing with our chess server, after writing the first draft of the implementation we may want to separate things to different modules - the original module is probably quite long at this point.

+ chess/

config/

+ lib/

board.ex

chess.ex

interaction.ex

move.ex

player.ex

test/

mix.exsLevel 1: Chess server folder structure.

All modules, except the main one – Chess, should be prefixed with Chess. – the name of our (Elixir) application. This helps with visually distinguishing our code from dependencies, and also clearly shows that Chess is an entry point. For example, the module for board:

defmodule Chess.Board do

defstruct [:white_pieces, :black_pieces, :cells]

def init_board() do

pieces = all_pieces()

%__MODULE__{

white_pieces: Enum.map(pieces, fn p -> {:white, p} end),

black_pieces: Enum.map(pieces, fn p -> {:black, p} end),

cells: init_cells()

}

end

# TODO:

def checkmate?(new_board), do: false

## Helpers

defp all_pieces() do

[:king, :queen, {:rook, 2}, {:bishop, 2}, {:knight, 2}, {:pawn, 8}]

|> Enum.flat_map(fn

{piece, count} -> List.duplicate(piece, count)

piece -> [piece]

end)

end

# TODO:

defp init_cells(), do: nil

endIt’s important to separate public API from the helpers, and make sure that we expose as little as possible. Public API should always be documented, and typespecs will also improve things in the long term.

Also, resist the desire to import all the things. Prefer alias as much as possible. When you alias something, you can easily find all the cases where functions on a given module are called, and names of those functions also may be improved. For example, at first we can directly translate our main module to use the submodules:

defmodule Chess do

alias Chess.{Board, Player, Move, Interaction}

def play() do

play(Board.init_board(), Player.first_turn_player(), 0)

end

def play(board, player, turn) do

move = Interaction.read_move(player)

case Move.execute_move(move, board, player) do

{:ok, new_board} ->

if Board.checkmate?(new_board) do

Interaction.declare_victory(player, turn)

else

play(board, Player.next_player(player), turn + 1)

end

{:error, illegal_move} ->

Interaction.report_illegal_move(player, illegal_move)

play(board, player, turn)

end

end

end

However, you can clearly see that naming of those functions may now be improved: Move.execute_move and Board.init_board are a clear tautology, there’s no need to repeat _player in each Player module function, and we don’t need verbs for Interaction functions anymore as well:

defmodule Chess do

alias Chess.{Board, Player, Move, Interaction}

def play() do

play(Board.init(), Player.first_turn(), 0)

end

def play(board, player, turn) do

move = Interaction.read_move(player)

case Move.execute(move, board, player) do

{:ok, new_board} ->

if Board.checkmate?(new_board) do

Interaction.victory(player, turn)

else

play(board, Player.next(player), turn + 1)

end

{:error, illegal_move} ->

Interaction.illegal_move(player, illegal_move)

play(board, player, turn)

end

end

endAbility to improve names like this is one of indicators of good modularity: each module has a prime responsibility, so nouns may often be skipped.

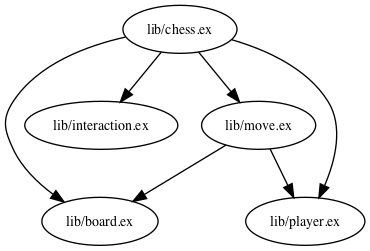

We also may want to visualise dependencies between modules with the help of xref at this stage (see instructions on how to do that in the end of the post):

Level 1:

Level 1: xref dependency graph.

We may notice and remove some dependencies that can be easily avoided if we do that. There isn’t anything unusual at this stage in the chess app, though.

If a module has a primary struct / data type that it works with, we should write a @type t :: ... spec. Naming the primary type as t is a convention in both Elixir and OCaml. Structs define a type with this name on creation.

When to use: for small apps, e.g. small command-line tools, implementations of more complicated algorithms, etc.

Level 2. Modules with submodules

A collections of modules, some of which have submodules (e.g., App.URI may have App.URI.Parser as a submodule, and use it internally).

A modules with submodules often works as a kind of an entrypoint, and submodules are rarely used directly (if not counting structs and protocol definitions) from other parts of the system. Often this is organised as a folder with all the “interface”/entrypoint modules at the root, and subfolders with submodules are created for those interface modules that need them.

Example: imagine, that now we want to provide a play against computer mode. We can add a Chess.Robot module to the root folder of our app, but the logic required for making that work will eventually require separation into several submodules. We may arrive to a structure like this:

+ chess/

config/

+ lib/

+ robot/

evaluator.ex

generator.ex

selector.ex

board.ex

chess.ex

interaction.ex

move.ex

player.ex

robot.ex

test/

mix.exs

Nobody apart from Chess.Robot should use Chess.Robot.Generator, Chess.Robot.Evaluator, and Chess.Robot.Selector. By putting them in a directory with name robot we indicate that those are submodules of the Chess.Robot module.

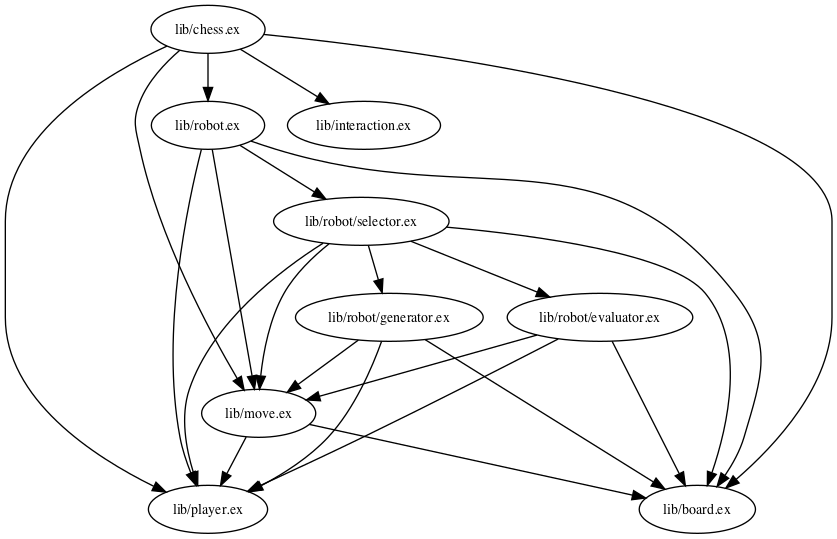

We can use xref again to see dependencies between our modules:

Level 2:

Level 2: xref dependency graph.

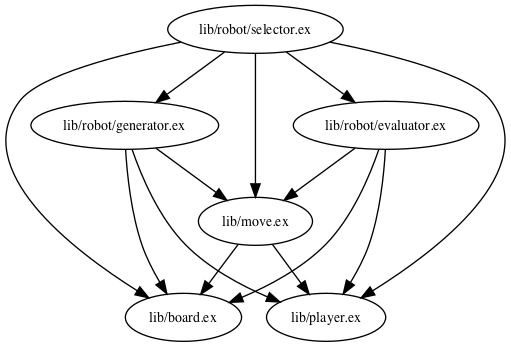

Let’s see only the dependencies of Chess.Robot with source option: mix xref graph --source lib/robot.ex --format=dot:

Chess.Robot module dependencies graph

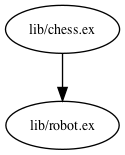

And we can see the modules depending on Chess.Robot with sink, as in

mix xref graph --sink lib/robot.ex --format=dot:

Modules depending on

Modules depending on Chess.Robot graph

We also may notice that most modules that depend on Chess.Board also depend on Chess.Player – maybe it’s time to add current player to the Chess.Board struct? Looking at the dependencies graph is often useful to spot a possible refactoring like this.

Another things to watch for is cyclic dependencies between modules. You should generally avoid creating those. Cyclic dependencies can always be refactored by either merging mutually dependent modules together, or (better in most cases) - introducing another module, that will use both of mutually dependent modules and provide public interface. In more fancy words: your dependencies graph should be acyclic.

For example, if A is mutually dependent with B, you can introduce C, and make A and B its submodules.

When to use: libraries, somewhat larger apps than in level 1.

Level 2.5. Contexts

Now, if you take restricting access to a bunch of connected submodules, and allowing different parts of the app to call only so called context modules from each bunch idea, you’ll get Phoenix Contexts. Though they were popularized by Phoenix, this way of structuring application is used in a lot of Elixir apps, even if they don’t use Phoenix. I suggest you follow the linked Phoenix docs for the full explanation of this idea.

Quite often this context-based code organization pattern leads to a bunch of functions in the context module assuming roles of delegates for the functions from submodules. Gladly, Elixir has a macro for that specific case: defdelegate.

One important caveat of contexts in Elixir is that the language doesn’t yet posses an ability to define private modules. This may be annoying when using plain submodules as well, but it’s even more of a problem when using contexts – though you put a lot of effort in separating concerns, you cannot really enforce this separation as of yet. This problem has been discussed on the ElixirForum, but no concrete decision has been reached. For now, tools like xref may be useful for checking context integrity manually or via scripts.

Example: assume that now we want to make a web app out of our chess server. We can generate a new Phoenix project to do that. If we want to keep console client as well, we can choose to create an umbrella project. If only web interface will be provided, we don’t need to do that.

We then can move our existing logic to the Chess application – just by copying the files from the old console app. We won’t need Chess.Interaction module anymore – ChessWeb application will do its job now. Since we’ve separated side-effects from logic since the beginning, it should be easy enough to provide a basic game state storage and API on top of the logic we already have.

We may start by introducing a Chess.Game context. We can start with something like mix phx.gen.context Games Game games player:string board:map.

We can still keep Chess.Board on the top level of the Chess application, or we may create a separate context for it – depending on the code size. We shouldn’t move the Board module into the Game context without consideration, though – all our logic in Move and Robot will probably depend on it, and database-related functionality is not very useful for those.

After saving the game state to the db, we can provide corresponding APIs for retrieving it, and APIs for players to make moves. Also, our Chess.Player module will probably be a different thing from our User module. Game though should know who is playing white and black pieces, and if one of the players should be a Robot.

We’ll arrive to a directory structure similar to this (only showing lib folder):

+ lib/

+ chess/

+ games/

game.ex

+ robot/

evaluator.ex

generator.ex

selector.ex

+ users/

user.ex

application.ex

board.ex

games.ex

move.ex

player.ex

repo.ex

robot.ex

users.ex

chess_web/

chess.ex

chess_web.exChess Phoenix application folder structure

Now, we may want to clean that up a bit, for example by creating Chess.Logic context for the chess-specific game logic and structs:

+ lib/

+ chess/

+ games/

game.ex

+ logic/

board.ex

move.ex

player.ex

+ robot/

evaluator.ex

generator.ex

selector.ex

+ users/

user.ex

application.ex

games.ex

logic.ex

repo.ex

robot.ex

users.ex

chess_web/

chess.ex

chess_web.ex

Better folder structure with Logic context

You also may notice that our structure continues to be nice and recursive: we’ve got two applications Chess and ChessWeb, each with an upper-level context module in the lib directory. ChessWeb is structured according to the MVC pattern, but Chess is just our normal Elixir application – it shouldn’t know anything about the web part.

Each context in the Chess application is at the root level in lib/chess subdirectory, and all submodules of each context are in the folder with the same name as the context. For example, Chess.Logic.{Board, Move, Player} modules live in the Chess.Logic context, so we’ve got logic.ex in lib/chess, and board.ex, move.ex, player.ex in lib/chess/logic folder.

When to use: most webapps, and medium+ sized apps

Level 3. Behaviours

Behaviours specify a fixed interface that different modules can implement. This is useful for providing swappable implementations of different parts of the system (you can pass a module as a normal value in Elixir, remember?), executing inversion of control-like patterns, defining explicit interfaces for critical inflection points, and testing.

Using behaviours earns as an upgrade on the modularity levels ladder by a virtue of explicitly defined contracts between modules/subsystems.

Behaviours often require some kind of a dispatch module on top, especially if you use them to define an interface for swappable implementations of the same functionality – the client code may like to call it like this: Dispatcher.some_fun(implementation_module, args, ...). In other cases, you may want to call behaviour implementations modules directly – this depends on your specific goal of using behaviours.

Another common theme is defining a __using__ macro in a behaviour that will provide its default implementation. Behaviour callbacks are then marked as defoverridable where applicable to provide customisation capabilities for users of the behaviour. You can see a good example of this in the GenServer code.

Example: we may want to integrate a 3rd-party chess AI instead of our own Robot, but we may still want to keep Robot as a fallback in case the 3rd-party AI becomes unavailable. We can achieve this by introducing an AI context defining a Chess.AI.Engine behaviour. Then we may change our robot.ex to implement this Engine behaviour, and add [Insert3rdPartyAINameHere] context, also implementing the same behaviour. In lib/chess/ai.ex we can define the functions that will dispatch to the selected Engine, or implement fallback mechanism that will first try to call 3rd-party AI, and if the call fails, use our own implementation from Robot.

When to use: library interfaces (like Plug, GenServer, …), inversion of control, swappable implementations of some functionality inside larger apps, testing integrations with external systems.

Level 4. Actors

We’ve reached the highest possible level of decoupling one part of a code from the others: giving it its own failure semantics and state storage by using an actor.

Now, some may be surprised that I include visibly unrelated concept in the discussion about modularity. I don’t think that this concept is unrelated. Actors are modules, and whole supervision trees (groups of modules) may be organised via Module with Submodules or Contexts. Yet, actors provide something that ordinary modules don’t: they may store state they control themselves, and have special failure/supervision semantics.

This earns us another level up: now we can make sure that failures in some parts of the code will not cause other parts of the same app to fail. Since actors don’t share state, they also make us think about information dependencies between parts of the system more.

Furthermore, supervision trees and public APIs of actors tend to influence folder organization and modular structure directly. Contexts tend to work very well for that.

At the same time, actors are only needed where state storage, concurrency, and failure semantics are required. Using them in a name of theoretical “decoupling” is definitely an overkill.

Example: our chess example already uses actors, though so far indirectly - Phoenix will create an actor for each request, separating failures in one request from other requests. Of course, nothing prevents us from adding our own actors whenever we’ll need them as well. No changes to our folder organisation strategy are necessary, since actors are also modules.

When to use: when failure isolation, concurrency, or stateful behaviour are required.

Level 5. Applications and Umbrella Projects

That’s the final level that we can reach inside one Elixir codebase. Applications can be started as a single unit, have a centralized supervision tree, and specified dependencies. Umbrella projects are often used to separate related applications, and also to have some library code that is shared between those applications.

It’s worth noting that using separate applications and umbrella projects does introduce additional complexity, thus it cannot be recommended for standalone small apps.

Example: by using Phoenix we’ve already split our app in two applications: Chess and ChessWeb. I think that Phoenix is kinda exceptional here: most of the time you don’t need to think much about those applications, apart from avoiding introducing dependencies from Chess to ChessWeb, so for me this is still level 2.5.

However, imagine that we’d like to add a chatbot client for our chess server. We can then convert our Phoenix project into an umbrella, and add another application Chessbot. We will need to be careful and avoid introducing dependencies between Chessbot and ChessWeb – gladly, we can always extract any common code by creating another library project inside the umbrella.

When to use: separate components inside one Elixir system, several small apps sharing the same problem domain, etc.

Level 6. Components

Finally, if we need to have some non-Elixir code, or if we have some external components that we don’t control, we may need to switch to using fully separate components. Ditto for microservices. Those components would typically have HTTP/GraphQL/RPC/Messaging APIs, may be written in different languages, and generally require some kind of orchestration to run them all.

One of main pros of this design (if executed correctly) is an ability to provide significantly higher uptime and throughputs than non-distributed apps. It’s also possible to also scale engineering team faster with this approach, since multiple components can be developed independently.

This, of course, multiplies complexity by a power of magnitude. Apart from making decisions about how to structure those related components, how to orchestrate and monitor them, you also need to be mindful of a whole new world of failure states that comes with distributed programming. As in the famous quote (popularized by Leslie Lamport in 1987):

A distributed system is one in which the failure of a computer you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable.

At the same time, Elixir together with OTP provides a solution for those hard distribution questions, which is probably the best in terms of developer productivity and reliability. Applying it correctly is still non-trivial, but having tools for that in the standard library is a huge win over many competing languages.

Also, if distribution in itself is required, but the app can be completely (or almost completely – by using ports and NIFs you can sprinkle other languages in mainly-Elixir app) written in Elixir, you may not need to go so far – in fact, most Phoenix apps are both distributed and at the level 2+/3.

Example: we may want to extract our own Robot logic into a separate component and make it available for other users from our company. We will probably need to separate it into its own mix project, or convert our existing project to an umbrella. We will also need to add some kind of IO - either an HTTP API, or connection to a message broker, or something like that. We should be mindful of still separating IO from the pure logic, of course.

When to use: when the app grows really large, and you have a lot of engineering to develop it. May be unavoidable in multiple-language environments.

Special case: Dispatch through configuration

There is a useful pattern on decoupling parts of the system via configuration that seems to become quite popular as well - using configuration with {Module, Function, Arguments} tuples to provide essentially static, but at the same dynamic from compiler’s point of view, dispatch via Kernel.apply/3.

Since compiler doesn’t know about this dependency, it cannot track it, and tools like xref cannot help either. At the same time, this provides higher level of decoupling between parts of the system. Thus, it’s not a way to structure your whole app, but it is useful for some subsystems inside a larger app.

When to use: this works especially well for things like periodic tasks executors, event subscribers to messaging systems like RabbitMQ or Kafka, etc. inside the larger app. Generally, whenever you have some non-standard execution required for some statically known functions, and you don’t want to couple the execution logic with the functions that will be actually run, this is a good choice.

Architecture shouldn’t be set in stone

Most Elixir apps will start at level 2.5 or higher, especially if they use Phoenix. Most libraries will not require going further than level 2.

At the same time, apps tend to grow in size over time, and applying modular design at any level will help when upgrading to the next level is required.

Behaviours and actors fit seamlessly into Modules with Submodules or Context designs, so those changes are usually localized.

If module boundaries were respected, and the number of dependencies between modules was minimized, extracting modules, groups of modules, or contexts into another application (and possibly converting project to an umbrella) should be easy to achieve. If later you’ll need to extract something as a separate component, it shouldn’t be too tough either.

On the other hand, not caring about modularity in any sufficiently complicated app will make both of these a tough job.

No “just in case” design

Yet, there’s no need to over-engineer a solution from the start. Modular techniques quite often introduce indirection, which makes reading and reasoning about code tougher.

It’s the same kind of defensive programming as putting try/catch everywhere – you’re still likely to need to refactor something down the line, but you’ll just have more code to reshape.

Tools that are helpful for tracking and improving modularity

Gladly, Elixir comes with a bunch of highly useful tools that help with designing modular applications:

-

xrefhas already been mentioned, but it’s worthy of an additional endorsement. Apart from creating module dependencies graphs and stats viagraphmode, it can also show all the callers of a module/function withcallersmode, and all the unreachable/deprecated parts of the code viaunreachable/deprecated.mix help xrefis a good place to start learning about it :) -

To get graphs like in this post, you’ll need to call the following magical incantation inside a Mix project:

mix xref graph --format dot, and then you can get a PNG of the graph from the dot file withdot -Tpng xref_graph.dot -o xref_graph.png. -

observeris invaluable for inspecting and tracing systems both in dev and in prod, but it also shows supervision trees in the Applications tab. Remember that modularity is about runtime dependencies as well? You can easily simulate failures withobserverby killing some actors from the interface. -

typespecs and

dialyzerare very helpful for designing good modules and tracing type dependencies between those modules. Use them!

If you enjoyed this content, you can sponsor me on Github to produce more videos / educational blog posts.

And if you're looking for consulting services, feel free to contact me .